Nick J Fox

Introduction: aerial governance!

Over 20 years ago, when a government White Paper entitled The New NHS. Modern. Dependable (Dept of Health 1997) descended on to clinicians’ desks, few had a clear understanding of the meaning of clinical governance, let alone the scope of the project.

Today, this phrase is part of the everyday parlance of the health service. Furthermore, it is clear that clinical governance is everybody’s business (Department of Health 1998: 31).

Let me illustrate this with an analogy.

Imagine that you are taking a flight with your favourite airline, or maybe your favourite can’t supply the flight you need, so you have taken another carrier which serves your intended destination. Either way, you hope to have an uneventful flight and arrive safely.

Apart from a ticket and boarding pass, a receipt for checked baggage, the safety leaflet and maybe a menu for the in-flight meals, it is unlikely that you will have other documents pertaining to the flight, and particularly the safety standards of the plane. But you would expect such documentation to exist, and that bodies such as the UK Civil Aviation Authority would be regularly checking this out. The kinds of thing you could expect to be available might include:

- Certification of airworthiness, and documents about the commissioning of the airplane into service, safety checks and maintenance records;

- Conformance to industry and legal standards, both for the airplane itself and such issues as working hours, conditions of work and safety regulations (for instance, ensuring pilots are not inebriated);

- Documents concerning the training of the crew, including both initial and in-service training (for example around safety procedures and competencies such as language the skills to communicate to air traffic controllers and knowledge of terminology), and information on procedures to ensure skills are regularly updated;

- Manuals and other guidelines for staff, both for routine matters and for emergency situations;

- Adequate strategic management procedures to ensure quality of all aspects of the flight, including policies on risk management, clear lines of responsibility for safety, and processes of accountability for errors. It might also involve details of business planning: the insolvent or loss-making airline is unlikely to be as safe as the one which is well capitalised.

Passengers would hardly wish to have to wade through all this material before taking their seats. But the expectation that these guarantees of safety procedures both exist and are seen by a regulator within a process of audit will reassure you about the likelihood of a safe journey. (You might also be encouraged by the more nebulous sense that the airline’s employees are motivated and enthusiastic about their work, though this in itself would not guarantee safety in the absence of other processes.)

This analogy should illustrate some important features of governance, both of an airplane journey and of a health service. First, though safety cannot ever be guaranteed one hundred per cent, benchmarking quality of products, processes and activities against high standards will minimise risk.

Second, governance procedures are intended not to correct errors after they happen, but to avoid them happening in the first place. This means a commitment to continuous quality improvement.

Third, the successful outcome of an activity (a flight, an episode of treatment of a patient) depends on a myriad of interlocking factors, and requires participation in quality procedures by everybody. The flight attendant who has forgotten the safety drill endangers emergency procedures even if everyone else plays their part effectively. The lack of adequate supervision of a junior doctor can be the weak link in the chain. (The responsibility of the passenger or the patient for her/his own actions may also be acknowledged here: users have a part to play in assuring the safety or quality of an activity, and must be involved in quality assurance procedures.)

Finally, the governance of an activity depends not only upon having systems of quality assurance in place, but also that these systems can be demonstrated to be in place and effective. Governance, by demonstrating quality to a regulator on behalf of ‘the public’ releases individual passengers or patients from the onerous task of evaluating the procedures employed by an airline or health service before using it. As such, governance is a marker of responsibility or accountability for the quality of service, and as such may be considered central to the professional and ethical obligation which a provider has to her/his client.

Perhaps the most valuable lesson from this analogy between health care and air travel is that the kinds of governance which are being proposed for health services are taken for granted in other areas. Indeed we would be horrified if such procedures did not exist for a hazardous business like flying aboard a commercial airplane. Health care, which can have life or death significance for its consumers, surely deserves the kind of governance which we expect elsewhere.

Clinical Governance: What’s the point?

The pathfinder definition of clinical governance, which first appeared in A First Class Service (Department of Health 1998), identifies the key elements of clinical governance. Clinical governance is:

‘… a framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish’.

The first important point is that clinical governance comprises a series of interlocking processes which together contribute the outcome of governance of health care. We will look at the process elements which are part of this framework later in this guide. It follows that clinical governance is an outcome, rather than an act in its own right: only if all the constituent elements are in place, will we achieve clinical governance.

The three key components of clinical governance thus are:

- A system of accountability and responsibility (by organisations, but we might add, individual clinicians also). Within the clinical governance framework, chief executive officers (CEOs) of trusts are ultimately accountable for the clinical activities and quality of care in their organisation. To make such accountability workable, the basic structure of a clinical governance lead (a clinician) and a sub-committee will take responsibility for ensuring quality and that standards are met. They will report to the Board of the trust or PCO, and contribute to the annual clinical governance report. The accountability of the CEO goes hand-in-hand with the responsibility all clinicians have for delivering excellent care.

- A commitment to continuous quality improvement (CQI) n the delivery and management of health care. It is not sufficient to meet a target and then sit back on one’s laurels. CQI entails the continual aspiration to surpass targets and then identify higher standards for service delivery. CQI depends on excellent professional and personal skills, interprofessional team working and continuing professional development. It means that standards will steadily rise across the NHS.

- A system for ensuring standards are set and met (for example through risk management and the management of performance). Standards are defined by combining available research evidence on clinical effectiveness, clinical expertise and patient and user feedback. Meeting standards depends on having effective systems of audit of clinical activity; where they are not met, action plans for improvement and re-audit are implemented. Setting national standards reduces variation in service delivery.

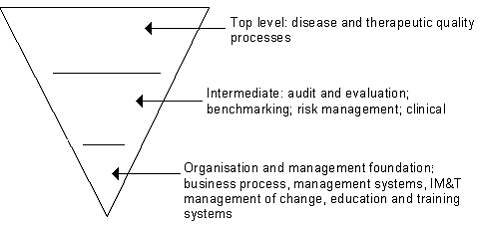

Clinical governance has as its objective excellence in the delivery of clinical care. This is the only rationale for clinical governance: it is not an end in itself, nor a management exercise to rationalise use of resources or staffing (although, as will be indicated in the next section, clinical governance could be used in these ways). This framework is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

So what’s the point of clinical governance? To answer that question, imagine some time in the future, when guess what – the NHS has been transformed by the system of clinical governance! Here is a case study; a patient who belongs to Somewhere Medical Centre, part of the Anywhere primary care group (PCG).

Mr A is a 55 year old married man with a history of breathlessness, hypertension and occasional mild angina: all risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD). Three months ago he was prescribed prophylactic statins (lipid-lowering medication) after a full work-up by Dr B in the primary care setting showed his serum cholesterol figures were high. In addition he has been given a diet sheet to help him lose weight. Mr A is attending for his follow-up with the practice nurse at Somewhere Medical Centre. On examination and fasting blood test, his symptoms have reduced and his blood lipids are now within an acceptable range.

Firstly, considering the management of Mr A’s condition, we can see that:

- Dr B, the general practitioner, has followed the National Service Framework for management of CHD in primary care, and locally produced guidelines from Anywhere PCG These guidelines were developed following a risk management exercise, taking into account the local circumstances surrounding referrals into secondary care and resource allocation.

- Before prescribing statins to her patients, Dr B had consulted a database of research evidence on clinical trials of these drugs available from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, using her NHSnet connection. She is also able to use this to participate in an electronic forum on CHD which includes cardiology specialists and primary care clinicians

- The use of the Electronic Patient Record enables confidential sharing of information across the PCG (every clinician has a networked PC on her/his desk). Mr A’s data automatically contributes to the clinical audit of management of CHD in primary care being undertaken by the Group as part of its continuing effort to improve its service delivery in this and a number of other key areas.

- These data are included in the annual clinical governance report by the PCG. The data are also used to benchmark the PCG against equivalent primary care groups, and to increase its standards for the stable management of CHD year on year. In one or two cases in the past, it has also been used to identify clinicians who were under-performing in certain areas, to enable remedial education and support. Last year, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) visited the PCG as part of a rolling programme of external monitoring. This routinely gathered data informed the documentation prepared for the CQC visitation.

Other circumstances pertinent to this case study:

- Dr B has undertaken a course in the management of CHD in primary care as part of her re-accreditation process. All members of the PCG staff have annual appraisals which identify needs for continuing professional development (CPD) and continuing medical education (CME). There is protected time for staff to undertake CPD, CME and other courses. Dr B studies part-time for a Master’s degree, and human resource planning provides flexible work patterns to enable access to education and training.

- Over the past ten years, three members of the PCG Board, including the Chief Executive, the Chair and a nurse member have gained MBA qualifications by part-time study at the local University. They are facilitating a series of workshops on risk management and performance management to snowball their knowledge and skills across the PCG.

- Somewhere Medical Centre clinicians hold case conferences each month at which staff reports critical incidents. Team-building workshops have contributed to a no-blame culture in which errors and variations in service delivery can be aired openly. Each incident is subjected to review to improve processes of service delivery. The review is documented and shared across the PCG using the trust’s intranet (an electronic communication network within an organisation).

- Staff participate in ‘quality circles’ which cut across traditional hierarchies and encourage initiatives from all those involved with patient care, including reception and administrative staff. One proposal from a quality circle meant that Mr A was able to book his appointment via the Internet, enabling him to plan his work schedule around it.

- Mr A was part of a focus group of patients from across the PCG who were consulted about service delivery in the trust. Reports from these consultations are considered by the clinical governance sub-committee, and included in the sub-committee’s report to the PCG Board.

- The PCG has employed an information officer who can undertake Medline searches for research data for clinical staff, both to support clinical activity and as part of research studies being undertaken by a number of staff members. The information officer also manages the intranet and offers IM&T training and advice. He is responsible for collating data routinely collected during clinical work, to inform the annual reports and internal reviews of performance. He is line managed by the clinical governance lead for the PCG.

A little bit too perfect? Well not really any more, after 20 years of clinical governance. In fact, the case illustrates my argument that clinical governance is not a single process, but comprises a range of activities, all of which have the patient, and the excellence of service delivery at their heart. We can see the key elements here:

- Accountability: the information management systems and case conferences, appraisal system and mechanisms for addressing under-performance make all clinicians and the organisation accountable for the quality of service delivered. Annual reports on quality enable transparency of quality of care. There is expertise in management skills which is being disseminated throughout the PCG.

- Continuous Quality Improvement: a culture of quality improvement, openness about errors and variability in service, user involvement, quality circles and programmes for CME and CPD enable standards for quality in care to be continually surpassed and raised. These processes are underpinned by excellent information management systems and an explicit strategy for minimising risks and addressing adverse outcomes.

- Safeguarding high standards:care is delivered according to National Service Frameworks, and within the context of evidence-based practice and locally-developed guidelines on disease management, which include risk assessment. Quality of service delivery and internal systems and processes are audited and benchmarked against appropriate organisations, and responsiveness to under-performance through flexible workforce strategies and continuing education programmes minimise variation in quality. Clinical governance annual reports and the Care Quality Commission reviews monitor standards.

And the bottom line? Excellence in care is the point of these interlocking and inter-dependent systems and processes. Mr A is receiving excellent care, but this cannot be put down to one element. It is the consequence of processes which assure high standards are met, continually improve on those standards and accept responsibility for quality service delivery.

Self Assessment Question 1

Why do proponents of Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) talk about reducing variability? Surely medicine is an uncertain and variable business?

Reflective Exercise

List the processes contributing to clinical governance that were identified in the case study above which are already in place (even if they need a little tweaking) in your organisation. How do they impact on your own practice as a health professional?

You might wish to use this list as a basis for your study of further units in this course.

What clinical governance is not

Having broken down the definition of clinical governance, and then built it up again through the case study of Mr A, the logic of clinical governance should be clear. But before moving on to look at some components of clinical governance in greater detail, let us return for one moment to the analogy with an airplane journey, to conduct a ‘risk assessment’ on clinical governance itself. Risk assessment is an important part of any planning process, to see what could go wrong, and help protect against avoidable mistakes.

It should now be possible to recognise the congruence between the systems which might assure a high standard of safety on an airplane flight, and the kind of quality assurance which Mr A’s care reflects. But a cynic might see the documentation of safety procedures on a flight as most useful after an airplane crash! Certainly, they would be extremely valuable to the airline’s solicitors at the compensation hearing, to justify their safety record and shift the blame elsewhere.

But that is not the point of governance. Governance is not intended as a means of justification after an undesirable outcome, it is intended to prevent an outcome being undesirable. It is concerned with quality assurance not quality control. No doubt it can be used sometimes as a post hoc validation, but the spirit of clinical governance is in the other direction.

Clinical governance can and should be used positively, and – with the commitment of all clinicians – it can deliver its objective of assuring excellence in patient care. But there are associated risks, which derive from clinical governance’s capacity to be subverted in a variety of ways. It is worth setting out some of the positive characteristics of clinical governance and associated risks. If we are aware of the ways in which the spirit of clinical governance can be upended, we can ensure that it does not become just another fad or fashion, to be derided as no more than a management tool. Box 1 makes some comparisons between what clinical governance should and should not be.

Box 1: Two approaches to clinical governance

| Clinical governance should not be: | Clinical governance should be: |

| A system for responding to errors, or for justifying errors as unforeseeable | A system for assuring quality and avoiding errors/reducing variations |

| A top-down exercise, taken on by a clinical governance lead in each unit | An activity in which all staff are actively involved, under the leadership of a designated and accountable individual |

| An extra task to be undertaken alongside clinical or managerial duties | Integral to the everyday activities of clinicians, managers and other staff |

| A low priority activity which attempts to whitewash over the cracks in the ‘real business’ of treating patients | A high priority activity which clinicians recognise enables excellent care to be delivered uniformly across the NHS |

| A yearly management exercise resulting in a report on a trusts quality activities | A process (like an audit cycle) of review, planning, action, showing and sharing |

| A system requiring an entire new system of internal monitoring | Built on systems which are already in place and can be adapted and expanded to achieve clinical governance |

| A means of ‘shaming and blaming’ under-performing individuals or units | A means to encourage openness about errors and a commitment to work collaboratively and across the NHS to improve service |

| An erosion of self-regulation | A way of encouraging a culture of accountability among all clinicians |

| Something which is achieved once-and-for-all, and is thereafter set in stone | A developmental process which is responsive to changing circumstances |

| Tagged on to existing organisational arrangements in the NHS | Consequent upon a culture shift in the NHS, based on the principles on this side of the table. |

The right hand side of this table is thus a wish-list for clinical governance, the left-hand side is a list of risks – subversions of clinical governance which will undermine and destroy its rationale and its capacity to deliver excellence of care.

Reflective Exercise

Think about the positive and negative directions in which clinical governance could develop. Identify three areas in your organisation where clinical governance is being used positively.

Responding to the context: continuous quality improvement

The focus within clinical governance upon continuous quality improvement (CQI) and quality assurance draws on a well-established and contemporary perspective in management science that has a proven track record in both private and public sectors. Quality assurance seeks to reduce variations in a product or service, rather than responding to failures. CQI is based on organisational strategies that involve all members of staff in efforts to consider how to improve their contribution to the organisation’s output.

Clinical governance also builds on principles of corporate governance, which addresses issues of accountability in the running of organisations. These two bodies of theory together offer a mechanism for quality assurance in health care delivery which:

- provide a means to address equity across an organisation comprising many constituent units, while also setting in train processes to assure value-for-money in a service provided at tax-payers’ expense

- expands the concept of accountability from the corporate level to the level of clinical operations

- incorporates clinical risk management into the quality process, linking risk reduction to CQI.

- Addresses issues of performance management which assure standards are achieved.

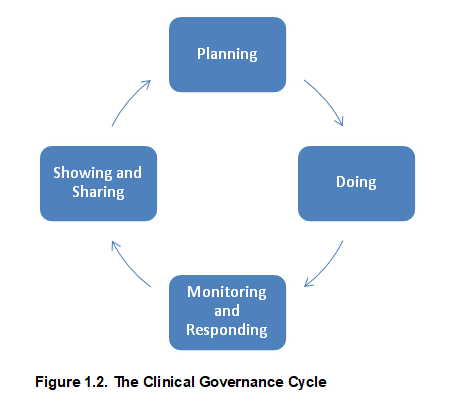

The CQI emphasis in clinical governance builds on clinical audit , which is now well-established in the NHS, but adding a fourth stage of showing and sharing to the three stages of standard setting, service monitoring and implementing improvements.

Implementing the Clinical Governance Cycle

By now, you should have a clear idea of what clinical governance is about; and the positive features of clinical governance. Earlier, we identified the three key elements of clinical governance, which we unpacked from the pathfinder definition: accountability, continuous quality improvement (CQI), and standard setting. As a review point, jot down the relevance of each for clinical governance.

Reflective Exercise

In clinical governance:

- Accountability is important because …

- Continuous Quality Improvement is important because …

- Standard setting is important because …

If you were not certain about any of these, check back now.

We can start to think about the implementation of clinical governance from the idea that it is something which is achieved. While there are various processes involved in clinical governance, it is itself in a sense an outcome, something which is either in place or is not. Knowing what is needed in terms of processes is the first step, however, clinical governance is achieved by the establishment of a cycle in which the stages of review and documentation are crucially important. Specifically, it is not enough to be doing quality assurance, one needs to be seen to be doing it. At the moment the cycle is closed, clinical governance is achieved, and not before: if the cycle is disrupted in any way, clinical governance is lost. This can be illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Descriptively, the stages are:

| Planning and setting standards | Agree objectives, benchmark against guidelines or research evidence, establish the process, make it explicit in the organisation through communication networks |

| Doing | Process implemented, including mechanism for data collection and audit. |

| Monitoring and responding | Set criteria for audit, collect data, compare against standard, formulate and implement action plan to correct errors or variations |

| Showing and sharing | Document cycle and share findings within and beyond the organisation, annual report and external monitoring |

In this cycle, we can see the three key elements of clinical governance. First, there is an adherence to standards , hence the need to benchmark and then measure activity against defined performance indicators. Second, there is the cycle of continuing quality improvement which entails monitoring and then responding to errors or variations. Finally, there is the accountability built into the showing and sharing phase of the cycle.

As trusts implement and demonstrate clinical governance, they may focus on very specific areas, such as the treatment of CHD or cancers. Over time, the elements of care for which there is clinical governance will increase, with the final objective being that all areas of clinical practice are subject to the governance cycle. Fortunately, the process is such that – once established in one clinical area – it will be easily transferable to other areas.

However, as was noted earlier, clinical governance amounts to more than just a glorified audit cycle. Indeed, the logic behind clinical governance is to enable effective audit and quality assurance, as the implementation of audit has been patchy in the past, and often seen as an end in itself, rather than as a mechanism for improvement. Clinical governance entails a cultural change, the purpose of which is to create the conditions under which CQI will result in excellent care. Cultural change is a challenge for trusts, and will often require specific new skills and training in change management.

By breaking clinical governance down into its components, and then taking this four-stage model of a cycle of governance, it is possible to detail the precise actions that will be required to fulfil the requirements of clinical governance. The following units in this course address the elements of clinical governance in more detail.

We begin by looking at educational issues, including continuing professional development and the use of the Internet for education. The following unit looks at the question of becoming evidence-based: a crucial element of benchmarking standards of care. The course then looks at involving the public in management of care, and addressing performance and under-performance: matters for improving the quality of care. Communicating risk to patients, and procedures for audit lead into a discussion of risk management and significant events audit, and the course is completed by considering data security and confidentiality.

We hope you enjoy the units that follow!

Self Assessment Question 2

Why is communication of risk to patients important for clinical governance?

Why is data security important for clinical governance?

Answers to SAQs

SAQ1

While it is true that all cases are different, we should be able to practice in such a way that all patients receive excellence in care. By aspiring to remove variability we do not mean that everyone gets the same care, but that all patients receive care free from errors, failures in procedure and skills, and independent of their personal characteristics.

SAQ2

a) Being able to communicate to patients the risks associated with a procedure is part of an evidence-based approach but it is also central to ensuring the quality of care and being personally accountable for ensuring patients make informed choices.

b) Clinical governance entails the gathering and analysis of data on patient care, organisation and procedures. The security of data is important first because it is a necessary factor in ensuring analysis is based on dependable information, and second, because sensitive personal information must be secure from third parties.

References

Department of Health (1997) The New NHS. Modern. Dependable. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (1998) A First Class Service: quality in the New NHS London: Department of Health.